A War Cry: Bethlehem - Micah 5:2-5a

Considering half the Island is already lit up, I feel safe asking

this question. What is your favorite thing about Christmas? Yes, I am talking about Christmas in a sermon

and it’s not even Thanksgiving. I got a

strange look from Kay when I told her I wanted to sing O Little Town of

Bethlehem this Sunday. It is not something I do without thought. I refuse to

play Christmas music at home or in the car until after Thanksgiving and I have been

known in some churches to be stubborn about Christmas music in church, telling

folks that in worship we had to wait until Christmas Eve, that the first four

weeks are Advent and not Christmas. However, as I have grown older, I have

become less legalistic about when we sing some music. With that confusion over, let me ask again,

what is your favorite thing about Christmas?

The lights? The trees? The candles?

The scents of pine, cedar, and a plethora of baked goods? The presents? The decorations? The cantatas?

The children’s programs? The worship? The carols? The parades? The family

gatherings? The movies? The stories? The

legends? Have I hit on it yet?

I love the lights—as a kid it was the colored lights, now I just

love the places lit up with all white lights.

I’ve shared with y’all before that has been a point of contention in our

household over the years, with my love of the white lights and Anita’s love of

the colors—at least until the year we found strands of lights that will

actually alternate between white and colored.

Many folks have their favorite extra-Biblical Christmas stories

and movies as well. I’ve heard quite a

few folks talk about enjoying all their favorite Hallmark Christmas movies. For

Anita it is Disney’s The Santa Clause,

for Joshua it is The Polar Express, I

grew up loving O’Henry’s Gift of the

Magi, and then fell in love with the Muppets updating it with Emmitt Otter’s Jug Band Christmas. One story or legend that I always marveled

at, though, was the story of Flanders, Belgium in 1914. It is the World War I story of how, despite

the fact that all involved sides dismissed the request by Pope Benedict XV for

a Christmas cease-fire, an impromptu cease-fire erupted between the British and

Germans in the trenches in the area of Flanders—initiated by the German

soldiers who set up Christmas trees and began singing carols, and eventually

involved both groups of soldiers entering the “no-man’s land” to share the

rations and gifts each had received, sing together, bury their dead together,

and even have a game or two of football (soccer). The peace lasted for about a week, when by

New Year’s Day, commanders of both groups of soldiers gave orders to resume

hostilities or face court martial.[i]

I share all of this because Christmas tends to be a time when we

think of peace and serenity amongst a rare snowfall with all the pretty lights

and celebrations. We dream of a perfect

white Christmas. What we forget is that very often for many people, Christmas

is a time of fear, depression, loneliness, desertion, and violence. The truth is, that despite the beauty of the

pageantry that surrounds Christmas, even in the church, that those of the

Biblical Christmas story—Mary, Joseph, the shepherds, the angels, and even

Jesus, it is this darker side of Christmas that they would come closest to

identifying with—a world filled with pain, misery, rejection, and sin. It is, in fact, this world of darkness and sin,

that the birth of the one who would later say, “Do not think that I have come

to bring peace to earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword,”[ii]

was not God’s declaration of “Peace on Earth,” but God’s declaration of war—a

war between God and Satan over the future of Creation—a war that begins in the

manger and ends on the other side of Easter with the empty tomb. My brothers and sisters, it is this

declaration of war that I want us to examine from this Sunday until the arrival

of the wise men (not on Christmas Day—but at Epiphany in January) as we journey

through this series entitled “A War Cry,” examining each of the familiar parts

of the Christmas Story, and reclaiming the Biblical truth and power of those

stories over the cute pageantry we have so often associated with the Christmas

Story—pageantry that sometimes gets it right, but often gets it wrong.

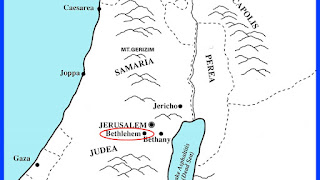

Today, let us begin, then, not with a person, but with a place, as

we examine God’s battle plan. It is the little town of Bethlehem. When you think

of Bethlehem what comes to mind? Small

town? The Nativity? A dark night with the star of Bethlehem shining overhead?

Maybe we even recall that outside the birthplace of Jesus, that it is also the

birthplace of David. Anything else? Do

we know anything else about this quaint little town? Is this it?

Are these the only times Bethlehem is mentioned? Actually no.

Looking closely at Bethlehem, we find that it is far from being a sleepy

little maternity ward for God’s chosen to be born.

In fact, as we turn to God’s Word, our first encounter with

Bethlehem is that of a birthplace, but also its exact opposite as well:

“Then they journeyed from Bethel; and when they were still some

distance from Ephrath, Rachel was in childbirth, and she had hard labor. When

she was in her hard labor, the midwife said to her, “Do not be afraid; for now

you will have another son.” As her soul was departing (for she died), she named

him Ben-Oni, (Son of my sorrow); but

his father called him Benjamin (son of my

right hand). So Rachel died, and she

was buried on the way to Ephrath (that is, Bethlehem).”[iii].

Our first Biblical encounter with Bethlehem is one not only associated with

childbirth, but with death connected to childbirth—it is a place of darkness,

death, grief…

Our next encounter with the town of Bethlehem is just as dark. We

encounter it in the book of Judges.

Without going into all the detail of Judges 17-19, because a graphic

description of what we encounter in those chapters would earn this sermon an

NC-17 rating; it involves idolatry, priestly faithlessness, abandonment,

betrayal, gang-rape, butchery, and death.

Bethlehem is also the hometown of Naomi, her husband, and their

sons. They left Bethlehem searching for

a more prosperous life. After the men took foreign women to be their wives, all

three men died. After their death, Naomi returned to Bethlehem with her former

daughter-in-law Ruth, and instructs those in Bethlehem who knew her to no

longer call her Naomi, but to call her Mara, which means “bitter.” She found

herself without any hope of a future because with no husband and no sons, she

had no hope of a future.

Even with the anointing of David in his hometown of Bethlehem, we

find it to be a place of discrimination—David, being the youngest of all his

brothers is completely disregarded when the prophet announces that he desires

to see all of Jesse’s sons. David’s young age leaving him ignored.

So this little town of Bethlehem—this place marked not only by the

darkness of night, but also by the darkness of death, sorrow, idolatry,

violence, and even prejudice, is the place where God sounds forth His war

cry—in the cry of a newborn babe laid in a manger.

What does God’s selection of Bethlehem mean to us? It means everything.

It means that where there is prejudice—whether it is ageism,

sexism, racism, classism, or any other “ism” that those who walk in God’s

creation have encountered—that God has entered into that darkness and called

for its defeat.

It means that where there is violence—not just war, but instances

of abuse, battery, rape, molestation, torture, butchery—that God does not turn

a blind eye, that God does not go somewhere else, but that God enters into that

very vile place and declares it will not last.

It means that where idolatry is found—anywhere that something

other than God is being worshipped, whether we are bowing down to wooden or

golden idols, statues of concrete or stone, or the more common idols of today,

fame, fortune, pleasure, and anything else to which we give more of our time

and energy than we do to God—God enters in and reminds us that He is God and

everything else will fail us as surely as a golden calf melts under heat.

It means that where sorrow is found—whether it is grief or

depression or a sense of abandonment—that God enters in and reminds us that we

are not alone---that He is with us, Emmanuel has come and we are never left

alone.

In means that where death is found, God chooses to enter that very

place, and claims victory, so that Paul is able to write, “Where, O death, is

your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?...But thanks be to God, who gives

us the victory through Our Lord Jesus Christ.”[iv]

My brothers and sisters, the fact that God chose to enter into the

darkness of Bethlehem and declare war means that we do not have to fear or be

ruled by fear of prejudice, violence, sorrow, or grief, and that we are called

to leave those idols behind that we may find ourselves in the company of the

One who has already won the war, and that with the empty tomb has given us reason

celebrate His birth with the lights of this season.

In the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment